Papyrological Institute

Blog Papyrus Questions

What can papyri teach us about antiquity? Students of papyrology in Leiden try to answer questions about life in antiquity aided by papyri from our collection.

By Nicoline Huijbrechts

Everybody knows fables, the little tales about (usually ) animals containing a moral. These fables can be used to teach moral truths to not only children, but also to adults. One of the definitions of the Oxford Englisch Dictionary (2023, Sense 2) is as follows: “A short story devised to convey some useful lesson; esp. one in which animals or inanimate things are the speakers or actors.” This definition is not universal, as fables are defined by Theon and Aphthonius in Antiquity as a fictional story, which is an image or allegory of the truth (Adrados 1999, 23). Furthermore, the genre ‘fable’ is an old one, as the earliest collection we know of, the collection of Demetrius of Phalerum, is dated to the end of the fourth century before Christ (Adrados 1999, 3). Since fables are mainly used nowadays as an educational tool for teaching moral lessons to children, it would be interesting to look at the possible educational purposes of fables in Antiquity. Were they used for educational purposes, and if so, how?

The function of the fable

Quintilian (1st century CE) gives a strong indication for the use of fables for educational purposes in his Insitution Oratione (1.9.2, Russell): Aesopi fabellas […] narrare sermone puro et nihil se supra modum extollente, deinde eandem gracilitatem stilo exigere condiscant [‘Let them learn to tell Aesop’s fables in pure and unpretentious language; then let them achieve the same slender elegance in a written version’]. In other words, the students learned to paraphrase Aesop’s fables and to write them down elegantly. These fables therefore played an important role in educating the students, not only for teaching moral truths, but they also functioned as writing exercises and as an introduction to the ancient culture (Kümmerling-Meibauer, 2006). As such, fables were used for multiple purposes in Antiquity.

The fable of the donkey

P.Leid.Inst. I 5 is an example of a papyrus with a fable that was used for educational purposes. Though the papyrus is broken away on both sides, the words καὶ ὄνος [‘and (the) donkey’] are clearly legible on the second line. Thus we know that the main characters of the papyrus are a donkey along with another animal, probably a lion. On the fourth line the papyrus reads ἐκ τῆς ἄγρας [‘of the hunt’] from which the conclusion can be drawn that the donkey is participating in a hunt. Furthermore, in lines 7-8 the words δευτ[έραν] and τρίτης [the ‘second’ and ‘third’ (share)] can be found, which helps us establish that the fable concerns the division of the loot. Through these elements, the fable has been connected to a fable also found in works of Babrius (2nd century), Phaedrus (1st century) and Ignatius Diaconus (8th century). Though these fables are very similar, there are variations between them. Babrius, for example, writes that the lion and the donkey go on a hunt, after which the lion claims the spoils, despite the spoils being divided into three shares (Fernández Delgado 2007, 323). In the version of Phaedrus, however, the donkey is absent. Instead, there are three other animals and the lion is the one without a share, despite the spoils being divided in four shares. Because, as stated by Quintilian, students were instructed to paraphrase the fables, the various versions of this fable may indicate the use of the fable for educational purposes. It is probable, therefore, that P.Leid.Inst. I 5 is such a school papyrus containing a paraphrase of this fable.

Teacher’s comments

A second clue for the use of fables in education is visible on the school papyri themselves, since the way that the papyri were written shows that the fables were used in all years of education (Laes 2006, 899). This can also be seen on P.Leid.Inst. I 5. Cribiore (1996, 239) states that the oblique strokes above some of the letters indicate that the fable was used as a reading exercise, since the strokes were used to indicate new words. Also, P.Leid.Inst. I 5 starts with the words ἀχαθῇ τύχῃ [’good luck’]. These words can be read as a good luck wish put by the teacher at the top of the papyrus (Daniel 1991, 8). These ‘good luck wishes’ have also been found on other papyri related to education (Cribiore 1996, 239).

Besides P.Leid.Inst. I 5, more papyri with fables are found that were probably used in education. One of these is Mper n.s. III xxx. This fable is about a weasel who tries to lure a mouse out of its hidey-hole (Oellacher et al. 1939, 51). This fable is described as an ‘Schulübnung,’ a school exercise in Oellacher’s edition, based on the form of the writing, the language and the content (Oellacher et al. 1939, 51). Clearly multiple fables all with different main characters, were used for educational purposes in antiquity.

Conclusion

In short, fables were used in Antiquity in multiple ways, since they were used as writing, language and reading exercises, as moral truths and as an introduction to cultural practices. This is further supported by P.Leid.Inst. I 5, in which reading indications are added to help the student learn to read and write, and the teacher added good luck wish to a student.

Bibliography

Primary sources

P.Leid.Inst. I 5 = R.W. Daniel (1991). In F.A.J. Hoogendijk, P. van Minnen & W. Clarysse (eds), Papyri, Ostraca, Parchments, and Waxed Tablets in the Leiden Papyrological Institute (Papyrologica Lugduno-Batava 25). Leiden.

MPER N.S. III xxx = H. Oellacher, H. Gerstinger & P. Sanz (1939). Mitteilungen aus der Papyrussammlung der Nationalbibliothek in Wien, Neue Serie. Volume III. Griechische literarische Papyri. Vienna.

Quintilianus, Institutio Oratione: D.A. Russell (2001). Quintilian. The Orator's Education, Volume 1: Books 1-2. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Secondary sources

Adrados, F. R. (1999). History of the Graeco-Latin Fable, Volume 1 (Mnemosyne Supplement 201). Leiden.

Cribiore, R. (1996). Writing, teachers, and students in Graeco-Roman Egypt. Atlanta, Georgia.

Fernández Delgado, J.A. (2007). ‘The Fable in School Papyri’. In J. Frösén, T. Purola & E. Salmenkivi (eds) Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Papyrology, Helsinki, 1-7 August, 2004, Volume 1. Helsinki. pp. 321-330.

Kümmerling-Meibauer, B. (2006). Children's and Young Adults' Literature (CT). In Brill's New Pauly Online. Leiden. https://doi.org/10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e1408880 [accessed December 17, 2023].

Laes, C. 2006. ‘Children and Fables, Children in Fables in Hellenistic and Roman Antiquity’. Latomus 65. Brussels. pp. 898-914.

Oxford English Dictionary. 2023. Oxford.

By Rosemary Selth

If one is to inquire about oracles in antiquity, they will probably be told about the oracles at Delphi and Dodona, or even the Sibyl in her cave from the Aeneid. However these were far from the only kinds of oracles found in antiquity. P.Leid.Inst. I 8, a papyrus fragment housed at the Leiden Papyrological Institute, is a unique fragment of the mysterious Sortes Astrampsychi, an oracle book of disputed origin. The text is made up of numbered questions and answers and primarily survives in Christianised manuscripts.

While most surviving fragments of this text comprise of oracle answers, this fragment is the only place which preserves the pre-Christianised concordance, the table which connects questions to answers. While this papyrus is not only invaluable for our understanding of the transmission and dating of the text, it is also a fascinating insight into oracular deities, with each concordance being accompanied by the name of a god. In this brief article, I’ll examine which gods were called upon to answer questions in this papyrus, and whether these gods are representative of oracular deities in general.

Introducing the gods

The concordance table is introduced with the phrase ‘gods who give oracles and signs.’ Each row after this contains a divine name between two numbers, the number on the left corresponding to a question, the number on the right corresponding to a table of ten answers. Unfortunately, the concordance preserved on this fragment is not completely intact – the bottom of the papyrus is lost so only half the table remains. Based on later manuscripts, we know that there should have been a total of 103 deities listed, but our fragment only contains 49. 7 of these are too damaged to read with any certainty, so we are left with 42 names. These are presented in the table below – the concordance numbers have been left out for the purpose of readability and mistakes in spelling and case endings have been corrected.

|

Gods who give oracles and signs Leto Sarapis Ischus (‘power’) Agathodaimon Ge (‘earth’) Astrapes (‘lightning’) Ephialtes (‘nightmare’) Eros (‘love’) Thetis Hekate ? ? ? ? Erinyes (furies) |

Athena Apollo Asklepios Aphrodite Ammon Anoubis Belos Boubastis Hera Dioskouroi (divine twins) Herakles Helios Dionysos ? Hephaistos ? ? |

Epitaktes (‘commander’) Muses Mithras Ourania Memphites Eunoia (‘benevolence’) Nymphs Mother of the Gods (Kybele) Klytios (‘listener’) Nike (‘victory’) Osiris Poseidon Parthenos (‘maiden’) Prosdokia (‘hope’) Ophelia (‘help’) Panakeia (‘cure’) Poros (‘means/possessions’) |

This list shows an intriguingly broad variety of deities. The majority is made up of major and minor Greek gods and heroes (e.g. Poseidon, Apollo, Asklepios, Ourania). Also included are six Egyptian deities (Sarapis, Agathodaimon, Ammon, Anoubis, Boubastis, and Osiris) as well as three other foreign deities - Belos, a Babylonian god; Mithras, an Iranian god; and Kybele, a Phrygian goddess. Also included are various personifications of abstract concepts (e.g. Nike ‘victory’, Prosdokia ‘hope’, Ophelia ‘help’). Lastly, there are several unusual names which appear to be epithets (cult titles) of gods that are otherwise unnamed (e.g. Epitaktes ‘commander’, a title that could refer to any number of gods). Of the 42 deities listed, only 13 have been established to have a previous association with divination. Specifically, these 13 deities are mentioned by Curnow (2004, 173-175) as having oracle sites in antiquity, but only three of them (Apollo, Asklepios, and Sarapis) have a large presence (the other eight deities being Ammon, Aphrodite, Dionysos, the Dioskouroi, Ge, Hera, Herakles, Leto, nymphs, and Poseidon).

Why these gods?

On initial reading, there is little else we can say about the choice of deities, especially as there is no connection between each god and the types of questions which were answered by them - an individual god in the concordance could be associated with ten completely different questions. What we can surmise is that this selection of gods may be so varied for the simple fact that there are 103 slots which needed to be filled on the concordance table. It is no surprise, then, that few of them have an explicit connection to divination. This is also potentially the reason that we see a lack of syncretism (the combining of deities). For example, Dionysos and Osiris are often considered to be one and the same, especially in Egypt (e.g. as described by Diodorus of Sicily, 1.13.1-1.20.6), but listing the two names separately would keep the composer from having to think of one extra name. This need for names may also be the reason for the inclusion of some rather obscure figures (e.g. Klytios, Memphites). However, there is much more to be understood about this selection of deities when we compare this list to other oracular texts.

Other oracles

Of particular relevance to this concordance are the western Anatolian astragaloi (knucklebones) oracle inscriptions (Graf 2005, 51-97). These inscriptions contain potential oracle answers prefaced by the name of a god, with each answer corresponding to a particular result from throwing five knucklebones. Graf (2005) identifies 19 such inscriptions, 13 of which are very closely related. Because of the attachment of a divine name to each answer, these inscriptions make a fascinating comparison to the Sortes. Although there are some clear differences to the Sortes concordance, such as the large number of repetitions (Zeus appears eight separate times with various titles), the makeup of gods is remarkably similar – the list of 56 deities is made up of Greek gods, Egyptian gods, other foreign gods, and personifications. 14 names from the concordance appear in these inscriptions (including non-Greek gods Sarapis, Kybele, Ammon, and Agathodaimon). It is also notable that the astragaloi oracle inscriptions all date around the end of the second century CE, the same period in which the Sortes Astrampsychi was likely composed (Stewart 1995, 135-147). One could also add to these examples a collection of oracle answers inscribed on ostraca (pot sherds) from Dios, all of which also date to around 200 CE and some of which also contain the names of gods (though due to their limited number, we can’t make any real observations as to the variety of chosen deities – Apollo, Leto, Typhon and Zeus) (Cuvigny 2021, 501-523). Considering the widespread nature of the astragaloi inscriptions and apparent popularity of these kinds of oracles during this period, we can perhaps make the argument that the Sortes Astrampsychi fits in with the larger tradition of popular oracles in the second century CE. If we accept this interpretation, the apparent mishmash of names on P.Leid.Inst.I 8 actually seems to be quite typical of oracular texts of this period.

Conclusion

To summarise, this Greek papyrus contains a fascinating selection of Greek gods, Egyptian and other foreign gods, personifications, and epithets. Furthermore, there is some intriguing comparative evidence which suggests that the variety of gods and personifications is quite typical for oracular texts of the second century CE.

Bibliography

Primary sources

P.Leid.Inst. I 8 = W. Clarysee & F.A.J. Hoogendijk (1991). In F.A.J. Hoogendijk, P. van Minnen & W. Clarysse (eds), Papyri, Ostraca, Parchments, and Waxed Tablets in the Leiden Papyrological Institute (Papyrologica Lugduno-Batava 25). Leiden.

Browne, G. M. (ed.) (1983). Sortes Astrampsychi I: Ecdosis Prior. Leipzig.

Stewart, R. (ed.) (2001). Sortes Astrampsychi II: Ecdosis Altera. Munich.

Secondary sources

Curnow, T. (2004). The Oracles of the Ancient World. London.

Cuvigny, H. (2021). ‘Chapter 31: The Shrine in the Praesidium of Dios (Eastern Desert of Egypt): Graffiti and Oracles in Context’. In R.S. Bagnall (ed.), Rome in Egypt’s Eastern Desert, Volume 2. New York. pp. 479-526.

Graf, F. (2005). ‘Rolling the Dice for an Answer’. In P.T. Struck & S.I. Johnston (eds), Mantikê. Leiden. pp. 51-97.

Naether, F. (2010). Die Sortes Astrampsychi: Problemlösungsstrategien durch Orakel im römischen Ägypten. Tübingen.

Rea, J. (1977). ‘A New Version of P. Yale Inv. 299’. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 27. Bonn. pp. 151-156.

Stewart, R. (1995). ‘The Textual Transmission of the “Sortes Astrampsychi”.’ Illinois Classical Studies 20. Illinois. pp. 135-147.

Stewart, R. & K. Morrell (1998). ‘10. Fortune Telling: The Oracles of Astampsychus’ In W. Hansen (ed.), Anthology of Ancient Greek Popular Literature. Indianapolis. pp. 285-324.

By Lisette Verhoeven

It might surprise you how much information papyri can give us about the ancient world. No matter the size of the scrap, it can help us reconstruct all kinds of facts of Greek life: even how music in Antiquity sounded.

Music played a prominent role and must have surrounded the Greeks at all times. Think, for example, of public festivals with singing processions or personal music-making during symposia. Also, performances of tragedies included choral or soloist songs. But how do we know any of this?

We have several sources that help us recreate the sound of Antiquity by giving us information about different instruments that were used (the first one can be dated back to 2700 BCE!) or development of the system of musical notation: think of depictions of performing musicians on vase-paintings, but also direct references to music-writing in literature. And not just that: the actual music that was played can be reconstructed thanks to remains of musical scores.

The Seikilos epitaph

A well-known example is the Seikilos epitaph (2nd century CE), a pillar inscribed with a small song for a funeral. Above the sentences we find musical notation. Unlike the system we use nowadays, the Greeks used alphabetic signs representing the pitches of the melody for the voice. Above these, there are linear symbols to indicate the intended duration of syllables and dots to specify the movement of the sung line. Thanks to this epitaph, we can make reconstructions of ancient sounds: https://antigonejournal.com/2021/12/song-of-seikilos/. If you listen carefully, you will notice that the melody respects the word accents almost everywhere and that the song is quite rhythmic. This would not be surprising, since Greek itself was an inherently metrical language. What a unique sound!

Iphigeneia in Aulis

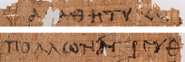

Now that we have seen some ancient musical notation on stone, let’s take it up a notch and look at a different surface, by which most fragments of ancient Greek music are transmitted: papyrus. The one that you see in the picture (P.Leiden Pap. Inst. inv. 510) dates from the 3rd century BCE, one of the oldest musical papyri transmitted to us. Even though it is small and damaged, we can still make out some letters and musical signs. This scrap contains parts of Euripides’ tragedy Iphigeneia in Aulis, which tells the tale of how the Trojan War started: with the sacrifice of Iphigeneia, daughter of Greek army commander Agamemnon. This horrible task had to be completed in order to appease the gods who, as a result, would grant a favorable wind direction, allowing the Greek army to sail to Troy and fight a legendary war. Interestingly, the text on our papyrus is not in the original order of the play. The first four lines are taken from Iphigeneia’s sung dialogue with chorus as she departs to be sacrificed, which would have taken place towards the end of the tragedy. Of these lines, the musical notation was not preserved, but given the space between the sentences we can assume that it would have been annotated originally. The other verses come from the second choral song, or stasimon, in which the Trojan War is described in vivid detail, and do contain indications for musical accompaniment. Even though these passages are not in the correct order (first lines 1500-1509, then 785-794), they both appear to have been dramatic moments in the storyline. The letters in bold are those preserved on the papyrus, while the rest of the text has been added to reconstruct the original.

1500-1509

Chorus:

Did you summon the city of Perseus,

carrying the hard work of Cyclops?

Iphigeneia:

You nourished me to be the light of Greece:

I do not refuse to die.

Chorus:

In that case, may glory not escape you.

Iphigeneia:

Oh! Oh!

Torch-carrying day

and light of Zeus, another

lifetime and lot I will inhabit.

Farewell, dear light.

785-794

Chorus:

Neither on me nor on the children of my children

may this hope ever befall,

such as those rich in gold,

the Lydians and wives of the Phrygians,

will acquire, beside their spinning wheels

they say this to one another:

“Who then, while straining me, a tearful

fence with well-braided hair,

will tear me away from my destroyed fatherland?”

Because of you, child of the long-necked swan, ….

Musical symbols

Not all musical symbols on this papyrus are clearly visible, which results in many different readings. However, we can agree on some things. As indicated on the photograph, we find notation (blue) in between lines: underneath μή and above πολύχ (red), there are signs that resemble C.T CT. These symbols do not look as fluent as the Greek letters, presumably because they were added later by a non-professional hand that was not as well trained. In terms of modern notes, these notations would have sounded like G and Gis. What is interesting, is that these signs are vocal as well as instrumental indications. We know about this difference thanks to another papyrus: Vienna G 2315 contains pieces of a different Euripidean tragedy, Orestes. The musical notation found here makes a clear distinction between notes for the singer, which were written above the text, and for the player of the instrument, placed in the same line as the sentences themselves.

The Leiden papyrus, however, solely contains musical notation above the text, including vocal and instrumental signs in the same lines. This would have made it difficult to decipher the difference between the two types of indications, but thankfully the Orestes papyrus helps us with this. It allows us to distinguish between the rounded C, a vocal notation written above the text of Orestes, and the squared C, which must have been an instrumental indication found in the Leiden papyrus. It is because of this comparison that we are able to come to such a conclusion and recreate the Euripidean tragedy as closely as possible: the Iphigeneia in Aulis-line would have been sung by a soloist accompanied by an instrument. Even though these songs were designed for the role of a female figure, it was typically interpreted by a male actor, in this case one with the vocal range of a tenor. In the Leiden papyrus then, we see that this Euripidean tragedy must have included music and, instead of a rendition of the entire play in the correct order, would have been performed in some kind of recital of musical highlights by a male singer accompanied by an instrument.

Conclusion

Ancient music sounded differently from ours, and it was also notated with letters instead of notes. We can reconstruct melodies in large part thanks to musical notation preserved on papyri. Surprisingly enough, little fragments give us the possibility to retrieve a lot of information about the performance of ancient Greek music in tragedies, even the way it sounded!

Bibliography

Primary sources

Pap. Flor. 43 (2) = Pordomingo, F. (2013). Antologias di Época Helenistica en Papiro. Papyrologica Florentina 43. Florence. pp. 65-68.

Vienna G 2315 = Pöhlmann, E. & M.L. West (2001). Documents of Ancient Greek Music: the extant melodies and fragments edited and transcribed with commentary. Oxford. pp. 18-21.

Seikilos Epitaph = Poljakov, F.B. (1989). Inschriften griechisher Städte aus Kleinasien (IK) 36.1 219. Bonn.

Secondary sources

Jourdan-Hemmerdinger, D. (1973). ‘Un Nouveau Papyrus Musical d’Euripide (Présentation Provisoire)’. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres 117e anneé 2. Paris. pp. 292-302.

Ceresa-Gastaldo, A. (1978). Problemi di Metrica Classica: Miscellanea Filologica. Genova.

Prauscello, L. (2006). Singing Alexandria: music between practice and textual transmission. Mnemosyne, Supplements Volume 274. Leiden. pp. 161-178.

Gammacurta, T. (2006). Papyrologica Scaenica: i copioni teatrali nella tradizione papiracea. Hellenica 20. Alexandria. pp. 14, 143-150.

Anderson, W. D. (1997). ‘From the Beginnings to the Dark Age’. In Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece. Ithaca, New York. pp. 1-26.

Barker, A. (1990). Greek Musical Writings. Cambridge.

D’Angour, A. (2017). ‘Euripides and the Sound of Music’. In L. McClure (ed.) A Companion to Euripides. Hoboken, New Jersey. pp. 428-443.

D’Angour, A. (2021). ‘The Song of Seikilos: a Musically Notated Ancient Greek Poem’. Antigone: https://antigonejournal.com/2021/12/song-of-seikilos/. Accessed 3-3-2025.

Hagel, S. (2009). Ancient Greek Music: A New Technical History. Cambridge.

Johnson, W.A. (2000). ‘Musical Evenings in the Early Empire: New Evidence from a Greek Papyrus with Musical Notation’. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 120. pp. 57-85.

Mountford, J.F. (1920). ‘Greek Music and its Relation to Modern Times’. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 40. pp. 13-42.

Pöhlmann, E. (2020). ‘The Regain of Ancient Greek Music and the Contribution of Papyrology’. In E. Pöhlmann (ed.) Ancient Music in Antiquity and Beyond: Collected Essays (2009-2019). Berlin. pp. 227-250.

Weiss, N.A. (2017). ‘From Choreia to Monody in Iphigenia in Aulis’. In The Music of Tragedy. Performance and Imagination in Euripidean Theater. Berkeley. pp. 191-232.

West, M.L. (1992). Ancient Greek Music. Oxford.

Winnington-Ingram, R.P. (1978). ‘Two Studies in Greek Musical Notation’. Philologus 122. pp. 237-248.