Research project

Tarsus

After the advent of Islam in the 7th century C.E., the strategic geographical position of Tarsus (its proximity to the sea and to the mountain pass leading to inland Anatolia) made this town the de facto capital of the thughur, a historical and geographical term created by Muslim geographers qualifying the Arab-Byzantine frontier. Subsequently, the city developed as a commercial and military metropolis with a cosmopolitan society including soldiers from all over the Islamic world as well as scholars and ascetics.

- Duration

- 2010 - 2016

- Contact

- Joanita Vroom

- Funding

-

VIDI - Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO)

VIDI - Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO)

- Partners

Bogazici University, Istanbul (TR): Tarsus-Gözlükule Archaeological Project

Historical background

Tarsus is situated in the southern part of central Turkey, 20 km. inland from the Mediterranean Sea. Tarsus was on the eastern border of the Byzantine Empire. It flourished as a trade and military centre because of its strategic location below the Cilician Gates, the main pass through the Taurus mountains of southern Turkey, connecting central Turkey, Syria and the Mediterranean coast. Captured by the Umayyads in 637 C.E., the city passed under Abbasid control in the 8th century and became one of the main centers of the Western thugur, the fortified region on the Islamic-Byzantine frontier. Tarsus attracted ghazis, volunteer soldiers of the Islamic faith from all over the Caliphate, stretching from North Africa to Iran, with provisions and accommodation provided by the support of the wealthy Muslim ruling class. The city was active in commercial activities, land and maritime trade and in the manufacturing of textiles, glass and ceramics. Since then, Tarsus frequently changed hands from the end of the 10th century onward among Byzantines, Armenians, Crusaders, Mamluks, Ramazanids and finally Ottomans and was used for naval operations by Byzantine, Islamic and Crusaders armies.

Excavations at Gözlükule

The first excavations on the mound of Gözlükule, situated in the south-western part of the city, was undertaken by an American team led by Hetty Goldman of Bryn Mawr College (U.S.). Supported by the Archaeological Institute of America, the Harvard Fogg Museum and the Institute of Advanced Study, the archaeological project was carried out from 1935 until 1939 and between 1947 and 1948. After a gap of almost 50 years, new excavations began in September 2001 with the collaboration of Bryn Mawr College (Pennsylvania, US) and Bosphorus University (Istanbul, TR) under the direction of Dr. Aslı Özyar. The excavations reveal that the mound was occupied from Neolithic to Late Ottoman times (c. 4500 B.C.E.-1900 C.E.). The Gözlükule Archaeological Project corresponds to one of the rare excavations in Turkey which has an extensive Early Islamic settlement and a considerable amount of Early Islamic to Islamic material finds.

The medieval and post-medieval ceramic material was previously examined by the American pottery specialist Florence E. Day, from the American University of Beyrouth, in the 1930s. However, this study was never published in detail. Recent research reveals that the largest quantity of the material dates to the Early Islamic period (mid. 7th-10th centuries C.E.).

The Ceramic Finds

The medieval ceramic assemblage from the old excavations is mainly composed of finewares. Tablewares include the broad range of polychrome glazed wares known as the “Samarra Horizon Pottery”, including Lustrewares, Opaque Glazed Ware with Cobalt Blue Paint, Glazed Relief Ware, Polychrome Splashed and Incised Wares, probably imported from the Abbasid heartland. In addition to the imported pottery, representing 20% the tablewares, the greatest group of the tablewares corresponds to a probably regionally produced Polychrome Painted Glazed Ware.

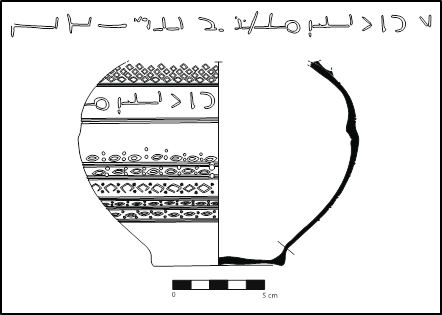

With 76% of unglazed pottery, light utility wares form a large group of the assemblage as well. These light utility ceramics used in the service of liquids are referred as “Unglazed Ware”. Unglazed Ware appears mainly in closed forms, and is commonly found in Early Islamic sites in the Near East. Among the cooking pots, there are two types. The first one is Brittle Ware, belonging to the Roman tradition, manufactured from an- iron rich, red clay, frequently shaped as medium-sized containers with concave walls. The second type corresponds to Soft Stone Vessel Imitations, which are made of a grey/black fabric. This group includes medium-sized pots with straight walls and lug handles, burnished on the exterior surface and decorated with incised geometric forms.

This specific material culture belonging to a widespread Muslim koinè raises political, socio-economic and cultural questions about the role of Tarsus in the military organization of the Abbasid Caliphate, about its role in the medieval international trade system, and finally about Muslim culinary habits.

Results & conclusions

The PhD candidate Yasemin Bağcı examined the Medieval ceramic corpus of the Tarsus- Gözlükule excavations between 2011-2015. Her research is included in her PhD dissertation “Revisiting the Medieval Ceramics of the 1935-1948 Gözlükule excavation in Tarsus, South Turkey.” In fact, this pottery material was uncovered on the mound of Gözlükule during the 1935-1948 American excavations directed by Prof. Hetty Goldman Tarsus, south Turkey. In 2001, the Gözlükule Archaeological Project resumed with the collaborative efforts of Boğaziçi University (TR) and Bryn Mawr College (USA) under the supervision of Dr Aslı Özyar. The Gözlükule Archaeological Project corresponds to one of the very few sites in Turkey that include an extensive Early Islamic stratum and especially an Abbasid settlement.

Although other excavations were conducted in Tarsus, very few of the Medieval material was published. The ceramic and other artifacts uncovered on the Gozlukule mound are tied almost exclusively to the Early Islamic tradition. This situation stands in contrast to the historical sources mentioning the lively trade between the Arabs and the Byzantines. Further, the absence of Early Islamic ceramics on the other side of the Taurus Mountains in Central Anatolia may suggest an overlap of the geographical boundary (the Taurus mountains surrounding Cilicia) with the cultural boundary of the Abbasids.

Including high quality finewares, the ceramic assemblage of Tarsus is comparable to the pottery finds recorded in major Abbasid sites such as Samarra (one of the Abbasid capitals) in Iraq, and Siraf (a major Abbasid entrepot) in Iran. This ceramic material thus testifies for Tarsus as a consumption site of significant weight tied to the economic system and the cultural koiné of the Abbasids stretching from Europe to Asia. This picture contrasts sharply with the historical sources frequently associating Tarsus with a peripheral frontier city switching hands between the Byzantines and the Muslims.

Follow-up

The medieval ceramics of the Gozlukule Tarsus excavations will be published in Yasemin Bağcı’s PhD dissertation “Revisiting the Medieval Ceramics of the 1935-1948 Gözlükule excavation in Tarsus, South Turkey.” in 2015.