Minecraft in Morocco: virtual building blocks bring the past to life

Getting young people excited about history is quite possible without books. Researchers from Leiden travelled to Morocco to work with schoolchildren on reconstructing cultural heritage in the popular video game Minecraft. The result: one virtual 14th-century city gate – and 20 teens with a greater appreciation for the past.

Wonderful things can happen in academia when different disciplines join forces. This year the university therefore awarded 33 ‘Kiem grants’ to help researchers start collaborative projects with colleagues from other faculties. One such grant went to a team of Leiden archaeologists, heritage specialists and digital culture experts. Their idea brought together not only multiple disciplines but also past and present: a virtual dive into history in the immensely popular online construction game Minecraft to bring Moroccan cultural heritage to life.

Together with the NIMAR expertise centre, the researchers contacted a secondary school in the northwestern port city of Salé. They asked 20 schoolchildren there to recreate the historic Bab el-Mrissa city gate in one afternoon as it would have looked in the 14th century. Not with craft materials but with building blocks in a digital world.

Lego for the new generation

But first a step back, because what do online video games and cultural heritage have to do with each other? A lot, says assistant professor and archaeologist Aris Politopoulos. ‘Take a game like Assassin’s Creed, which is set in a fictional history and has sold millions of copies. You can use games in all sorts of ways to share knowledge about archaeology, heritage and the past – and thus study what impact this has. At first glance, Minecraft might seem to have little to do with the past, but it is a game full of creative potential. A kind of Lego for the new generation.’

In Morocco, however, the goal was not so much to put each virtual building block in the right place. Sybille Lammes, Professor of New Media and Digital Culture, explains that the team mainly wanted to explore what a game like Minecraft can do for people’s appreciation of heritage. ‘It’s about collaboration and asking “what if” questions about the past. We asked the young people to think creatively about how the past might have looked.’

‘Heritage is made together: essentially it’s about talking to each other and sharing stories’

This combination of history and play produced curiosity and connections. Most pupils did not know at first there was such a (originally maritime) gate in their town, but after the virtual recreation, they wanted to know more about it. They discussed the ships that would have once passed through and shared pirate stories they had heard from their parents. One of the teenagers even said that from now on he was going to make sure that people would not drop litter at the gate. ‘You saw not only more appreciation but also a growing awareness that heritage is made together’, says associate professor Angus Mol. ‘Essentially it’s about talking to each other and sharing stories.’

Playground for all

The team is still thinking about a follow-up project but is certain that this will once again involve Minecraft. ‘And we are definitely open to new collaborations with people who, like us, are interested in heritage and games’, says Mol. ‘The playground is open to everyone.’

The researchers see their Kiem project as a literal seed that will continue to grow. ‘This grant is a great incentive to seek out that interfaculty collaboration more often’, says Lammes. ‘We are grateful that we were able to carry out our project, which would not have been possible otherwise. Now there is a framework that we can move forward with and we are in contact with other possible partners in Morocco. It really has had a snowball effect.’

-

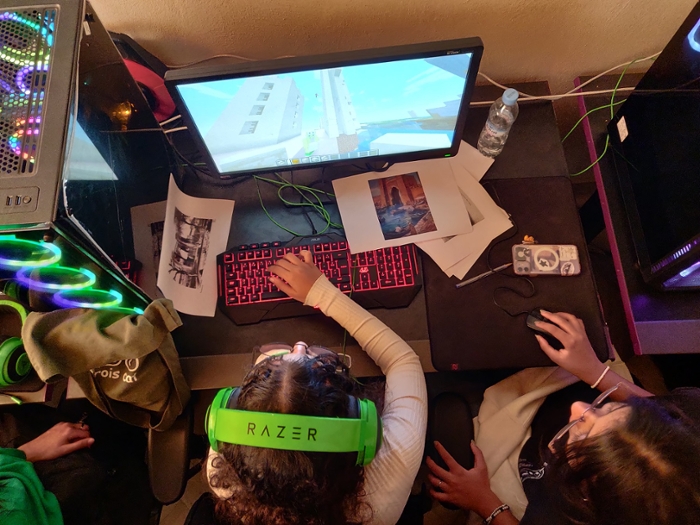

Two pupils hard at work in Minecraft. -

The group in front of Bab el-Mrissa. -

The group of schoolchildren, teachers, and Kiem project members in front of the city wall of Salé. -

Building in progress and supplemented historical and art material of Bab el-Mrissa. -

The group in front of Bab el-Mrissa with dr. Mohammed Krombi providing archaeological and historical information.

Text: Evelien Flink

Pictures: Crafting Heritage Experiences