Body's own marijuana helps us forget traumatic memories

The endogenous compound anandamide – often referred to as the body’s own marijuana – plays a role in erasing memories of a traumatic event. This was discovered by an international team led by Leiden chemist Mario van der Stelt. The results have been published in Nature Chemical Biology and may provide a starting point for the treatment of anxiety disorders such as PTSD.

Marijuana in your brain

When you smoke a joint, the active ingredient THC makes you feel relaxed. But there are also side effects, such as an increased appetite and loss of memory. ‘What about our body’s own marijuana? Does that have a similar effect?’, Professor of Molecular Physiology Mario van der Stelt found himself wondering five years ago. He decided to start a research line to find out, and received a Vici Grant from the Dutch Research Council in 2018. Two years later, in 2020, he and his team are the first in the world to inhibit the production of anandamide in the brain, thus revealing the true nature of this substance: it helps us forget traumatic memories and reduces stress.

Robotic arms to the rescue

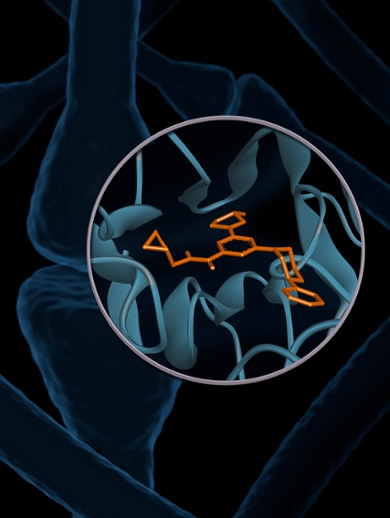

The research started in 2015 when Elliot Mock, first author of the publication and a PhD candidate at the time, and master’s student Anouk van der Gracht managed to get their hands on the protein NAPE-PLD. This protein is responsible for the production of anandamide in the brain. The next step was to find a compound that stops this protein from working. Because the idea was that if you inhibit the production of anandamide, you can study its biological role.

Finding such a substance turned out to be no mean feat. Van der Stelt turned to the European Lead Factory in Oss, the Netherlands, which was co-founded by his research group in 2013 and specialises in the rapid screening of hundreds of thousands of substances. He first had to secure EU approval before a fully automated system could start searching for the compound that inhibits the protein. ‘Actually, this involved 350,000 mini reactions, each with a different substance,’ says Van der Stelt. ‘They did so with the help of robot arms from the automotive industry. It took just three days to screen 350,000 substances, very impressive.’

Two years of lab-work

At the end of the screening, a hit emerged: a promising molecule to block the production of anandamide. ‘But this molecule wasn’t ready yet,’ says Van der Stelt. ‘So Elliot set to work on it.’ Mock optimised the molecule and, together with a number of students, spent two years synthesising over 100 analogues– molecules that differ slightly from each other. One of these eventually revealed the function of anandamide in the body.

‘We then started working with Roche Pharmaceuticals to analyse whether our optimised molecule reached the brain, an essential condition.’ By that time, cellular models had already pinpointed the analogue that worked best, and the researchers named this LEI-401. Roche then confirmed that LEI-401 does reach the brain. ‘Next, we and researchers from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the USA investigated whether our substance really works in the brain. That also turned out to be the case,’ says Van der Stelt.

Behavioural test

After three years, the way was finally open to answer the burning question: what is the physiological role of anandamide? This time Van der Stelt called on partners in Canada and the USA to investigate the physiological effects of reduced anandamide levels in the brain. ‘In animal models, LEI-401 meant that traumatic memories were no longer erased. In addition, the corticosteroid level was elevated and a brain region was activated that is responsible for the coordination of the stress response. From this, you can infer that anandamide is involved in reducing anxiety and stress.’

A new path

Van der Stelt’s research opens the way for new methods to treat anxiety disorders such as PTSD. ‘It is a starting point for the development of new medicines. As we have now shown that anandamide is responsible for forgetting anxieties, pharmaceutical companies can focus on a new target. And you then have two options: looking for molecules that stimulate the production of anandamide or looking for molecules that reduce its degradation.’

Endocannabinoids

The active substance in cannabis has been known since the 1960s: THC. In 1990, a protein was found that plays a role in the psychoactive effects of THC. These proteins are not present by chance, it turned out later. The body produces substances that resemble ones in cannabis: endocannabinoids. In 1992, Israeli chemist Raphael Mechoulam identified anandamide as the first endocannabinoid. Endocannabinoids play a role in a range of processes, from pain sensation to appetite, memory, blood pressure and movement. Two endocannabinoids are currently known: anandamide – the subject of this research – and 2-AG

Publication

Elliot D. Mock et al. - Discovery of a NAPE-PLD inhibitor that modulates emotional behavior in mice (2020), Nature Chemical Biology.

Text: Bryce Benda