Twinkle, twinkle, giant star

Up above the world so high a giant star twinkles. Could an 83-year-old astronomer unravel the mystery of this megastar? ‘At times I thought: that’s it! I give up! It’s beyond me.’

Oegstgeest

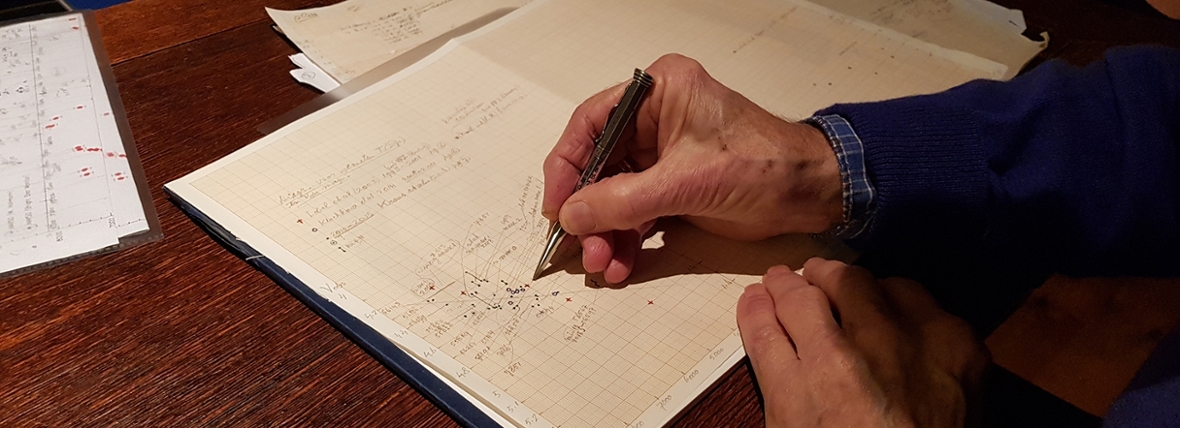

As night falls in Oegstgeest, a town just outside Leiden, Arnout van Genderen takes up position at his wooden desk in the corner of the sitting room. The 83-year-old astronomer takes a large sheet of squared paper and starts making small dots on it. This is how he has spent many an evening in recent years, working in silent concentration. If a noise distracts him, he just turns down the volume on his hearing aid.

Obviously there were times when he wanted to give up. Perhaps the mystery was simply too big and a person too small to solve it. But then he saw once again this ineffably large star that was making a beating motion somewhere up in the heavens, a bit like the old man’s heart beating in his chest. And he knew he couldn’t give up; he had to solve the mystery of the yellow hypergiant, a giant star about 600 times the size of our sun.

If a noise distracts him, he just turns down the volume on his hearing aid.

Over the past few years he has made thousands of dots on paper of this and other hypergiants, each dot representing the luminosity of a particular star at a particular moment in time. Plot all the dots next to one another on a sheet of squared paper and you get undulating lines of dots that give a good impression of the fluctuating luminosity of the stars. This could be done on a computer, but his painstaking manual labour brings a star to life on paper, says Van Genderen as he sets down a tray with two cups of Darjeeling on it. You get more of a sense of what is going on.

This is how the octogenarian has spent many an evening, at his desk that looks out on the ferns in his front garden. He goes to the University once or twice per week, mainly to ask the ‘clever clogs’ at the IT department for help. He shares an office with two colleagues who recently reached the ripe old age of 67, ‘young pensioners’ as he calls them. A bit of human contact does him good.

Dutch East Indies

Why doesn’t he sit back and enjoy his retirement? He is too much of a ‘born observer,’ he laughs. He still wants to see, hear, smell, taste and touch everything. It’s in his blood. From a young age already – growing up on a tea plantation in the Dutch East Indies – he saw the most miraculous things happening right in front of his nose. Why do climbing plants always grow in the same direction around a pole? And how do they know where to grow if they don’t have eyes? This could preoccupy young Arnout for days. Or in his own words: ‘I had a real thirst for knowledge.’

It was in a Japanese internment camp – Dutch citizens were interned during the Japanese occupation of Indonesia – that Van Genderen discovered his lifelong love: astronomy. Walking through the camp, he noticed that the moon always moved with him, whereas the trees behind the barbed wire fence soon disappeared from sight. He got his younger sister to stand 20 metres away from him and point to the moon and did the same himself. And guess what? Their arms were pointing parallel in the same direction. Later on, he discovered that without knowing it he had demonstrated parallax, a well-known natural phenomenon. While the conditions around him worsened, with a lack of food and medical care, he had just carried out his first scientific experiment, at the age of six.

His bedroom was packed with sea urchins and barracudas, giant clams and coral, fossilised wood and pieces of quartz, and slimy adders and boomslangs in specimen jars.

After the war he carried on collecting anything he could lay his hands on. His bedroom was packed with sea urchins and barracudas, giant clams and coral, fossilised wood and pieces of quartz, and slimy adders and boomslangs in specimen jars. He regularly dug up the skeletons of pets that had been buried in the back garden to get a better idea of their anatomy. And he and his father would compete in yacht races in Jakarta Bay. His job was to look at the wind direction, sea currents and cloud types and plot the best course. They often won with a lead of some lengths.

And his parents? They thought it was wonderful. When people came to visit, they would always give them a tour of young Arnout’s cabinet of curiosities, and they regularly brought home stuffed turtles, scorpions and seahorses from the local market, to pique the curiosity of their bright son. ‘They left me to my own devices and didn’t judge my fervent collecting. I’ve always been grateful for that.’

Leiden and South Africa

Fast forward to 1957, and Van Genderen had just begun a degree in astronomy at Leiden University. What until then had been a reasonably footloose and fancy-free little discipline suddenly went into turbo drive. Having just about recovered from the Second World War, the United States and Soviet Union plunged into a dizzying space race. The year 1957 also saw the Soviet Union launch the Sputnik, the first ever satellite. Conquering space – the final frontier of human discovery – suddenly seemed within reach. And Van Genderen was right in the midst of it all.

Having just about recovered from the Second World War the United States and Soviet Union plunged into a dizzying space race.

‘Sometimes it was 15 degrees below zero in the dome at the Old Observatory,’ Van Genderen remembers. ‘But I just put on two pairs of trousers and two jumpers and took up position at my telescopes in the roof. On clear evenings I almost invariably jumped on my bike, even if my housemates were sitting round drinking beer.’ He went on to earn his doctorate in photometry. With the aid of telescopes he measured the amount of light energy emitted by stars in order to document the changes in their luminosity and colour. This would help determine their distance.

Then Van Genderen was given a unique opportunity at the start of the 1970s: to move to South Africa – with his wife and daughter – to work for a few years at an observatory belonging to the Old Observatory. He ‘observed like there was no tomorrow,’ he says, there in that beautiful valley near Pretoria. But even after exhausting nights at the telescope he still found the time to look down at the ground every now and then because his broad knowledge was still not limited to the stars alone. He found pot shards, grindstones and other old objects. It didn’t take long until this ‘born observer’ had appeared in a South African newspaper, as the finder of the best-preserved prehistoric Bantu village in southern Africa.

Oegstgeest

Over the past four or five years, Van Genderen has been working hard to unravel the many mysteries of the yellow hypergiants. How can it be, for instance, that there are two variations in the luminosity and temperature of stars, a short changeable rhythm and a long irregular one? And what do the two versions actually represent? ‘At times I thought: that’s it! I give up! It’s beyond me.’

Then two of his colleagues discovered that the temperature of one of the yellow hypergiants fluctuated between 8,000 and 4,000 degrees Celsius, presumably because of atmospheric eruptions. And another colleague saw an opportunity to closely follow such an eruption and noticed that much mass disappeared into space. Could there be a link between these observations and the undulating patterns that Van Genderen saw on his squared paper?

Van Genderen may have been the principal author of the paper, but despite having reached the ripe old age of 83 he wasn’t the oldest member of the group.

The penny began to drop. Van Genderen ultimately calculated that all four of the yellow hypergiants pass through heat cycles lasting ten to a few dozen years. If the temperature increases, the hydrogen atoms lose their electrons causing the atmosphere to become very unstable, which in turn leads to an eruption. A lot of gas escapes in the process and in the space of two years the star cools to 4,000 degrees Celcius. The entire process then begins once again until the star, having lost a significant amount of weight, ends as a neutron star or a black hole.

Van Genderen and an international team of astronomers published the article in Astronomy & Astrophysics at the end of 2019. Van Genderen may have been the principal author of the paper but despite having reached the ripe old age of 83 he wasn’t the oldest of the bunch. One of his co-authors was the 98-year-old Cees de Jager, one of the fathers of Dutch astronomy. While the young Arnout was discovering astronomy in the Japanese internment camp, De Jager was already a student. He had gone into hiding in the vaults of Sonnenborgh, the observatory in Utrecht, during the German occupation of the Netherlands in the Second World War.

‘I have seen a phenomenal amount of change in astronomy,’ Van Genderen remarks as he looks back at his long career. ‘I was lucky enough to experience the exponential growth in knowledge and technology, from manual observations to punch cards and from magnetic tapes to automatic typewriters and observation techniques that are more modern still. In that time we humans have come to understand how we came about, where all that life comes from, all with just two kilos of brain in our heads. I’m seriously impressed and feel fortunate to have been part of it.’

‘We humans have come to understand how we came about, where all that life comes from, all with just two kilos of brain in our heads.’

He only has one regret: that this magnificent human brain is so often used for wrong. The Big Bang and the life that emerged was a miracle, but that we do not take proper care of this beautiful heritage is something he noticed while in the internment camp and in South Africa under Apartheid, and it is something he continues to notice practically every day when he opens the newspaper. No other animal is as cruel to its brothers and sisters as we humans – not even the snakes in jars in his Indonesian bedroom would have dared to kill one another. But for humans it is the very fabric of our being. ‘The contrast with our formidable brain is inexplicable.’

Text and photos: Merijn van Nuland

Mail the editors

About the co-authors of the journal article

Van Genderen wrote the article with the help of many fellow astronomers. Alex Lobel researches hypergiants and massive stars and works at the Royal Observatory of Belgium. Hans Nieuwenhuijzen worked at Utrecht Observatory and has been a guest researcher at SRON since 1998. Gregory Henry is an American amateur astronomer with an automatic telescope. Cees de Jager is the father of Dutch space research and a famous solar physicist. Eric Blown from New Zealand, Georgio Di Scala from Australia and Erwin van Ballegoij from the Netherlands are all amateur astronomers.

Van Genderen is also grateful for the help from his colleagues from the Leiden Observatory Computer Group, in particular Erik Deul, Aart Vos, David Jansen and Leonardo Lenoci.