Lorentz: celebrated physicist, born mediator

Emeritus professors Dirk van Delft and Frits Berends both channelled their inner Sherlock Holmes as they delved into the life and work of the great physicist Hendrik Lorentz. Their voluminous biography ‘Lorentz: gevierd fysicus, geboren verzoener’ (Lorentz: celebrated physicist, born mediator) is published on 25 October. What did they discover about this Nobel Laureate from Leiden?

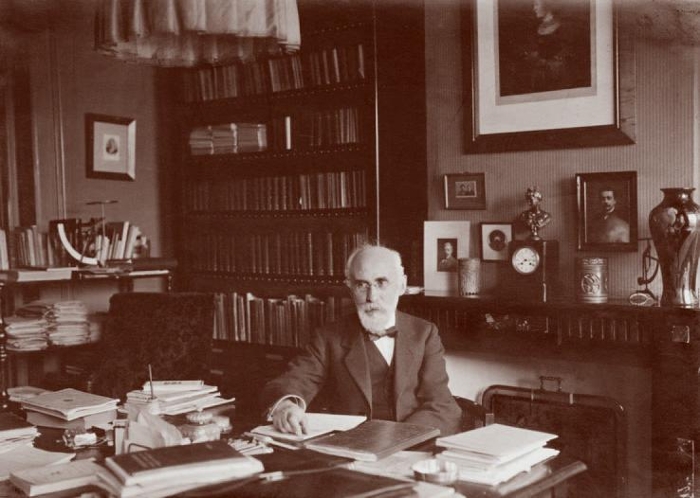

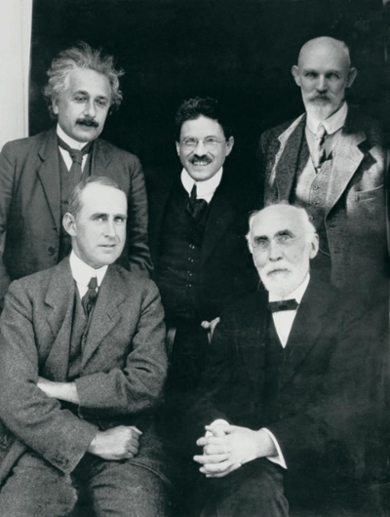

In the first quarter of the 20th century, Leiden became a real hotspot for physics. Numerous scientific discoveries were made and stars of international physics such as Albert Einstein, Max Planck and Marie Curie came to the city. Einstein in particular often kicked ideas around with the man whom he viewed as his mentor: Hendrik Antoon Lorentz (1853 - 1928). Lorentz was the tender age of 24 when he became Professor of Theoretical Physics, and together with Peter Zeeman he won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1902, for their research into the influence of magnetism on radiation phenomena. In the video below, author Dirk van Delft explains more about how important Lorentz was to science (article continues below the video).

Video [in Dutch]

Due to the selected cookie settings, we cannot show this video here.

Watch the video on the original website orDramatic developments

In this article, co-author Frits Berends explores Lorentz’s relationship with Einstein and Planck and sheds new light on his private life. Berends: ‘Lorentz was always seen as the son of a prosperous market gardener from Arnhem, but they weren’t that well off at all.’ The family had inherited a piece of land, but the archives show that they couldn’t live from this. Lorentz’s father Gerrit had a game leg, which meant he had to give up work as a market gardener. He became a carpenter and then a grocer, but with business bad he was forced to close the shop.

Another world

Fate continued to strike. When Lorentz was eight, his three-year-old brother died, followed by his mother Geertruida only six weeks later. In the civil records, Berends discovered that Lorentz’s father remarried six months after his mother’s death. Berends: ‘We can only guess at the impact of these events. They may link to Lorentz’s immense gratitude to headmaster Timmer, whose lessons he began to follow in the next year. Timmer took him to another world: the world of mathematics and physics.’

Blemishes

Lorentz was a very well-mannered person, says Berends. ‘But he was someone who kept people at a certain distance. He comes across as Mr Perfect, so as a biographer you look for the odd blemish here and there.’ For instance, how Lorentz tried to find work for his children. His daughter Luberta was good at physics and he supervised her PhD. Although not uncommon at the time, that would not be allowed today. Lorentz also tried – unsuccessfully – to arrange for translation work for her. In 1910, Lorentz was made curator of the Teylers Museum, which was also a scientific institute. He also held a post at the Royal Holland Society of Sciences and Humanities. His son Rudolf was made librarian at both institutions. ‘It’s striking, but nepotism is too big a word for it. You have to see it as a product of its time, a time in which there was no social security.’

Nobel Prize thwarted

With so much of Lorentz’s correspondence with peers such as Einstein and Planck preserved, the biographers were able to reconstruct many events. Berends gives the example of a lecture given by Lorentz at a mathematics conference in Rome in 1908. Here he said that although Planck had some fantastic ideas, he had proposed a hypothesis that was in conflict with physics at the time. Inadvertently, Lorentz thus thwarted Planck’s chances of winning the Nobel Prize. Swedish mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler had attended the lecture, and he was a member of the Swedish Academy of Sciences, which approved nominations for the Nobel Prize. The Physics Committee had just nominated Planck, but Mittag-Leffler after Lorentz’s lecture changed his mind. Coincidentally, Planck gave a lecture in Leiden on the day before the Nobel Prize that he had missed out on was awarded, and he even stayed at Lorentz’s house, on Hooigracht. The awkward incident had not affected their relationship. ‘They continued to enjoy an excellent friendship.’

Relationship between Einstein and Lorentz

Did the authors discover anything new about the relationship between Einstein and Lorentz? ‘Not much, but some nice details did emerge during the reconstruction work, and these can now be found in the book. They had a superb relationship. Lorentz was a kind of mentor for Einstein.’ In 1909, Einstein wrote to Lorentz: I’m impressed by your work. Lorentz replied that he had always been a strong admirer of Einstein’s work. He wanted Einstein to succeed him as a professor in Leiden. He invited Einstein to give a lecture there in February 1911, and the Einsteins stayed at his house. They visited the Teylers Museum together, where Lorentz showed them his laboratory. Einstein didn’t become Lorentz’s successor in the end, but he was made Professor by Special Appointment in Leiden in 1920.

Lorentz as mediator

The biography also takes a detailed look at Lorentz’s role as mediator. German researchers were not invited to conferences for years after the First World War. French and Belgian researchers refused to come if Germans would be there too. Lorentz was a member of a League of Nations committee that was tasked with rebuilding relations in post-war Europe. This was also his aim as chair of the Solvay Council in Brussels. The Solvay Council organised conferences for top international physicists, and in 1927 Lorentz managed to ensure that German physicists once again received an invitation. Berends: ‘That was vital because most of the developments in quantum mechanics came from Germany. With their revolutionary ideas, a group of young Germans made it an iconic conference.’

Lorentz and the particle accelerator

There are still echoes of Lorentz’s work today. Berends came into contact with Lorentz in his work as a physics professor. ‘I carried out a great deal of research into elementary particles and worked on the theoretical underpinning of the experiments with the particle accelerator in CERN. Elementary particles had not yet been discovered in Lorentz’s day, but we still owed a lot to his work. The particles in the accelerator are spun around in a trajectory in the vacuum tube by virtue of what is known as the Lorentz force. What is known as the Lorentz transformation – which expresses how to translate the properties of fast-moving particles into resting particles – is still used daily at CERN in collision analyses.’

Book

Lorentz. Gevierd fysicus, geboren verzoener, Frits Berends and Dirk van Delft (2019)

Prometheus Publishers

Photo above article: Noord-Holland Archives

Video: Sean van der Steen

Text: Linda van Putten

Mail the redactie

There was no real biography of Lorentz until October 2019. This month science historian Anne Kox published his biography about Lorentz: Een levend kunstwerk. Frits Berends: ‘Admittedly, it’s a real coincidence, two biographies about Lorentz in one month. I knew that a biography was being written, but also knew that there was still much to discover.’