Archaeology students explore visual culture with artworks

In a creative assignment as a part of the bachelor's course Visual Culture, students explored the impact and complexity of visual culture by means of visual culture. The resulting artworks were of such a high quality that it was decided to present these in an exhibition.

Material culture in ancient societies

The BA2 course Visual Culture analysed the complex, visual role of material culture in ancient societies and networks. The course focused on the Mediterranean (Egypt, Greece and Rome), the early Silk Roads in the Middle East (Petra and Palmyra), and cultural connections in Central Asia between the ancient societies of India (Gandhara and Gupta Empire) and China (Han and Tang Dynasties).

The course was one of the Byvanck courses of 2018, and was taught by Dr. Marike van Aerde.

The exhibition will be officially opened on May 7th, at 16.00 hours.

The six artworks

- Three Billboards along the Silk Road

- Neon Bamiyan Buddha

- Nefertiti in Perspective

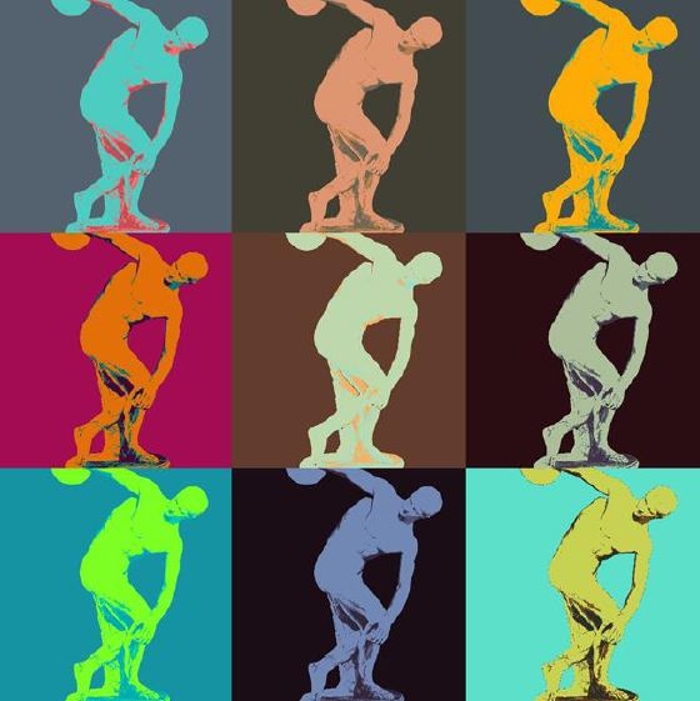

- Andy Warhol Discobolus

- The Gardens of Petra

- Etruscan Identity

Three Billboards along the Silk Road

Marian Leech, Mattia Lucca, Jessy Willemsen

During our research for the Visual Culture presentation, we were struck by the communicative power held by coins in antiquity. Coins, as vectors of exchange, had a high level of mobility and were probably one of the most efficient ways to reach a large portion of the population and transmit a message. Therefore, they not only held monetary value but they took on a parallel role as means of communication, propaganda and, what we can call, advertisement. Coins conveyed the power of politically influential individuals, regional religious beliefs and traditions, and important aspects of cultural identity.

Hence, we decided to extrapolate this aspect and translate it into a contemporary medium of communication. To speak to the high traffic and interconnectivity of the Silk Road, we relied on the billboard, an element embedded in the modern mobility network. The coins selected came from major centres along the Silk Road: Rome, Parthia, and the Kushan Empire. All the original elements of these coins were included in the design while additional features were added for design purposes, including colour and motifs which highlight specific cultural and political aspects of their respective societies.

Roman Coin: Silver; minted in Italy in 28 BCE, portrays Octavius and celebrates his recent conquest.

Parthian Coin: Silver: minted at Seleucia on the Tigris between 49-51 CE, portrays the King Gotarzes II and the goddess Tyche.

Kushan coin: Gold; minted in India between 127-150 CE, portrays the Emperor Kanishka the Great and the god Mozdoano.

Neon Bamiyan Buddha

Rishika Dhumal, Anna-Maria Mavridou, Kyra Tejero

To an ancient merchant travelling along the silk roads, this monastery was a place for rest and replenishment in a harsh, desert landscape. But in order to be visible to passing travellers, the enormous Buddha was built to draw attention. Just like a modern neon sign in the dark, this 53-metre-high statue was impossible to miss.

Our Neon Buddha is stylized, as are most neon signs, but is nevertheless clearly a Buddha thanks to the top knot and posture. Combined with red and light blue colours, which are very commonly used in neon signs, this Neon Buddha functions as a more contemporary version of a signboard.

Nefertiti in Perspective

Rowin Vaasen, Mark Top, Noud Visser

For our project we made two small, 3D printed sculptures of the world-famous Nefertiti busts. One of our sculptures was painted, just like the original, and the other was left white. We chose to do this because we wanted to showcase the effect paint can have on the perception of humans in sculptures.

Take for example the roman sculptures made out of marble. In our perception, the white statues are correct. However, they originally were painted just like the Amarna bust. By inverting this, taking a painted statue and making it white, we tried to make it clear that our perception of “what should be” is not always correct and often different as intended by the artist.

The Nefertiti bust was found in the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose and was in the Amarna style. The Amarna style was a short-lived art and belief system in ancient Egypt during the reign of Akhenaten and (possibly) Nefertiti. It was short lived because it drastically differed from what people saw as “normal”, such as stepping away from the polytheistic belief and adopting a monotheistic belief centred around the god Aton.

In art the style was typified by elongated heads, which can be seen on the Nefertiti bust.

Andy Warhol Discobolus

Claire Badart-Prentice, Kiyoka Koizumi, Jemma McGloin

The combination of two famous works - the discobolus and andy warhol’s marilyn monroe - is a reproduction that challenges the controversial definition of “copy”. The vigorous Discus-thrower by Myron was originally made in c. 450 BC in Greece, however only the Roman copy has survived. The statue was favoured worldwide and replicated overtime that even Hitler used this image for the infamous Berlin Olympics (1938).

Applying the method of Andy Warhol not only suggests the popularity and ideal beauty of the statue, but also casts questions to how it has been copied for centuries. Even though the original work was brightly colored most of the modern copies are left bare, which can lead to misunderstanding.

The Gardens of Petra

Sil Veenstra, Jannelin Wuisman, Koen Zijlstra

This project is based on the most recent excavations and interpretations of the Nabatean city of Petra’s complex water systems and resulting gardens and desert irrigation, which turned it into a wealthy nodal point in ancient trade networks. These drawings make use of archaeological studies as well as of an artistic exploration of the communicative role and impact of Petra’s desert gardens.

Etruscan Identity

Loes Hendricks, Maya Thorne, Will Wightman

This project explores the many complex layers that constituted Etruscan identity in Antiquity, and does so by gathering all different aspects as well as different interpretative perspectives on this topic in the form of a modern passport. Each stamp, each language and motif chosen here expresses elements that are crucial to the ongoing debate on Etruscan society and connects them visually.

Visit the exhibition

The artworks are displayed until October 2018 in the Van Steenis main hall, upper landing.